"Making sense of animal emotional states and behavior, especially when they are doing things that seem abnormal, has always involved a certain amount of projection. The diagnoses that many of these animals receive reflect shifting ideas about human mental health, since people use the concepts, language and diagnostic tools they are comfortable with to puzzle out what may be wrong with the animals around them.

This isn’t to say that the creatures aren’t suffering, but the labels we give to their suffering reflect not only our beliefs about animals’ capacity for emotional expression, but also our own, most popular, ideas about mental illness and recovery. Where, for example, earlier generations saw madness, homesickness and heartbreak in themselves and other animals, veterinarians and physicians now diagnose anxiety, impulse control and obsessive-compulsive disorders in humans, dogs, gorillas, whales and many animals in between" (ideas.TED.com).

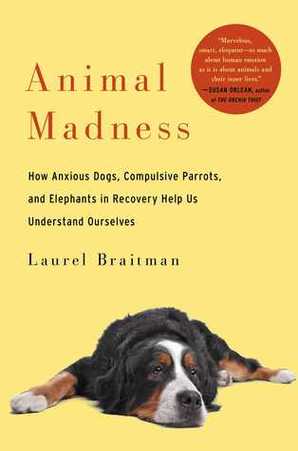

Recommended For:

Animal lovers, veterinarians, and anyone interested in human mental health!

For the first time, a historian of science draws evidence from across the world to show how humans and other animals are astonishingly similar when it comes to their feelings and the ways in which they lose their minds.

Charles Darwin developed his evolutionary theories by looking at physical differences in Galapagos finches and fancy pigeons. Alfred Russell Wallace investigated a range of creatures in the Malay Archipelago. Laurel Braitman got her lessons closer to home—by watching her dog. Oliver snapped at flies that only he could see, ate Ziploc bags, towels, and cartons of eggs. He suffered debilitating separation anxiety, was prone to aggression, and may even have attempted suicide. Her experience with Oliver forced Laurel to acknowledge a form of continuity between humans and other animals that, first as a biology major and later as a PhD student at MIT, she’d never been taught in school. Nonhuman animals can lose their minds. And when they do, it often looks a lot like human mental illness.

Thankfully, all of us can heal. As Laurel spent three years traveling the world in search of emotionally disturbed animals and the people who care for them, she discovered numerous stories of recovery: parrots that learn how to stop plucking their feathers, dogs that cease licking their tails raw, polar bears that stop swimming in compulsive circles, and great apes that benefit from the help of human psychiatrists. How do these animals recover? The same way we do: with love, with medicine, and above all, with the knowledge that someone understands why we suffer and what can make us feel better.

After all of the digging in the archives of museums and zoos, the years synthesizing scientific literature, and the hours observing dog parks, wildlife encounters, and amusement parks, Laurel found that understanding the emotional distress of animals can help us better understand ourselves (Goodreads.com).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed