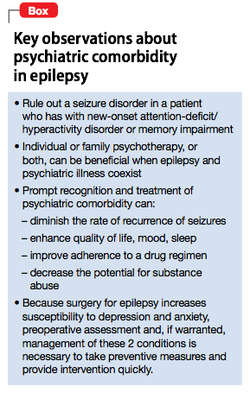

The tragedy in Isla Vista, California last weekend has raised a number of issues and of course has turned attention onto mental health and mental healthcare. However, as Globe and Mail author Leah McLaren reports in the must read article "The Elliot Rodger Case: It’s Time to Listen To Concerned Parents About Mental Illness", the case of Elliot Rodgers more importantly highlights the key role that families and especially parents play in managing and identifying mental illness. "The case of Elliot Rodgers highlights a central problem in the system, and that is the historic failure of authorities (be they mental health professionals or police) to listen, respond and be prepared to intervene based on the information supplied by the family and friends of young people suffering from mental illness." The mental health professionals interviewed in this article also stress how essential it is that we begin to listen to family members who often have more insight into their child's mental well-being, as well as encourage families to seek help early on when changes begin to arise, and help ensure psychiatry institutions and interventions are more family focused.  Dr. Stan Kutcher, professor in the Department of Psychiatry at Dalhousie University, talks about interventions that can improve mental health in developing countries, including "mental health by stealth" in the article "Global Health Must Include Mental Health". ""If we want mental health, we need healthy brains," according to Dr. Kutcher. Investing in mothers and their children from pregnancy through age three would improve brain development and decrease the prevalence of mental disorders, especially those that come from substance ingestion and malnutrition in protein and other key vitamins, he explains. From there, mental health interventions focus primarily on three objectives: tackling the deeply entrenched stigma against mental illness; developing mental health literacy among the general population; and building capacity at the community level to diagnose and treat mental illness with accessible primary-care interventions."  Andrea Wachter, a Licensed Marriage and Family Therapist, discusses her struggles with perfectionism and how always striving to be perfect can for some lead to anxiety, feelings of failure or inadequacy, and disruptions in their lives and relationships. Through her own experiences, Wachter also shares some advice on how to let go of the strict ideal of "perfect" so many of us have. "Confessions of a Recovering Perfectionist" by Andrea Wachter (Huffington Post)  Family physician, Dr. Kyle Bradford Jones, opens up and bravely shares his personal experience with mental illness, and encourages other physicians to seek help if they have concerns about their own mental health in his post on KevinMD.com. "Physicians avoid seeking help for many reasons, not least of which is concern about losing their job or practice. But it’s critically important to recognize the problems when they exist and seek help. We are much more likely to cause harm to others and ourselves when we avoid getting help. The stigma is sometimes difficult to overcome, but seeking proper services not only helps us, it helps our families, our friends and our patients."  Although an article about the state of mental health care in the United States, the story "The Cost of Not Caring: Nowhere To Go: The Financial and Human Toll For Neglecting the Mentally Ill" by Lisa Szabo describes the lack of adequate and effective support services for those with mental illnesses and the emotional, social and financial tolls that result, which likely occurs in other nations as well.  A Revolutionary Approach to Treating PTSD by Jeneen Interlandi is an interesting read on PTSD, and the conflicting views surrounding the best treatments for it. Specifically, the article interviews and comments on psychiatrist Bessel van der Kolk, and his somewhat controversial ideas about traumatic experiences, the effects trauma has on one's body which he believes the mind then follows, and his beliefs that alternative treatments such as psychomotor therapy, yoga, eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (#EMDR), are preferable as they focus on one's physiological state, which is often intimately connected to our stress response, emotions and mentality. "Trauma victims, van der Kolk likes to say, are alienated from their bodies by a cascade of events that begins deep in the brain with an almond-shaped structure known as the amygdala. When faced with a threat, the amygdala triggers a fight-or-flight response, which includes the release of a flood of hormones. This response usually persists until the threat is vanquished. But if the threat isn’t vanquished — if we can’t fight or flee — the amygdala, which can be thought of as the body’s smoke detector, keeps sounding the alarm. We keep producing stress hormones, which in turn wreak havoc on the rest of our bodies. It’s similar to what happens in chronic stress, except that in traumatic stress, the memories of the traumatic event invade patients’ subconscious thoughts, sending them back into fight-or-flight mode at the slightest provocation. Therapists and patients refer to this as being “reactivated.” In the short term, patients avoid the pain it causes by “dissociating ... The goal of treatment should be to resolve this disconnect. “If we can help our patients tolerate their own bodily sensations, they’ll be able to process the trauma themselves,” he says” (NY Times).  To Hell and Back: Alcoholism, Addiction and Lessons They Taught Me by Jim Coyle is a powerful must read story on addiction, alcoholism and recovery... "It's said around the circles of recovery that when we start drinking alcoholically, we stop growing emotionally. We suffer arrested development at the stage in which the addiction takes hold. This happens, it seems to me now, because we stop doing the things we need to do to grow up. First, we don't make decisions. In my case, I would attach myself to a girlfriend and let her make all decisions - then I had someone to blame if they didn't work out. Second, we don't accept consequences. We usually have two tools for relating to the world and the people in it - blaming and rationalization. There's always somebody or a workplace or an institution thwarting our plans for an ideal relationship, job, life. Nothing was ever our fault. Third, we don't truly feel pain, often life's best tutor. We're usually anesthetized, and always so in reaction to problems or crises, real or perceived ... Social drinkers might occasionally exaggerate their consumption, the better to pose as characters. Problem drinkers almost always minimize, covering their consumption in vague, comforting terms that make their drinking sound modest, unthreatening, almost wholesome, even patriotic. Denial is a powerful thing. The alcoholic-addict needs it to protect the sham sense of self he or she has constructed. A family troubled by addiction needs it to justify the sick contortions into which it has twisted itself to accommodate the bizarre behaviour of a loved one. Friends and co-workers play along with the con because, well, it's usually just easier that way" (http://rosemarykeevil.files.wordpress.com/2013/12/hell_and_backjpg-size-xxlarge-letterbox-version-2.jpg).  It is not uncommon for patients to have multiple comorbidities, including those that are physical as well as mental in origin. As most of us would guess, one illness can often have an impact on other aspects of a patient's life, including making management of other medical conditions more complex, and increasing the risk of developing further health issues. This sort of relationship has been seen between seizure disorders like #epilepsy and psychiatric disorders. In the resource, "Managing Psychiatric Illness in Patients With Epilepsy" by Sowmya C. Puvvada, Satyanarayana Kommisetti, & Abhishek Reddy, readers can learn how to distinguish between features of epilepsy and signs/symptoms of common mental health conditions (such as substance abuse disorders, sleep disorders, and anxiety), discover the links between seizures and mental illness, and learn the preferred management and treatment strategies for depression and psychosis among those with seizure disorders along with gaining other clinical pearls. "Patients who have epilepsy have a higher incidence of psychiatric illness than the general population—at a prevalence of 60%. Establishing a temporal association and making a psychiatric diagnosis can be vexing, but awareness of potential comorbidities does improve the clinical outcome. As this article discusses, psychiatric presentations and ictal disorders can share common pathology and exacerbate one another. Their coexistence often results in frequent hospitalization, higher treatment cost, and drug-resistant seizures. Risk factors for psychopathology in people who have epilepsy include psychosocial stressors, genetic factors, early age of onset of seizures, and each ictal event. Among ictal disorders, temporal-lobe epilepsy confers the highest rate of comorbidity" (Current Psychiatry). |

Description

Supporting and enhancing students' and health professionals' knowledge and understanding of mental health and psychiatry

Archives

June 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed