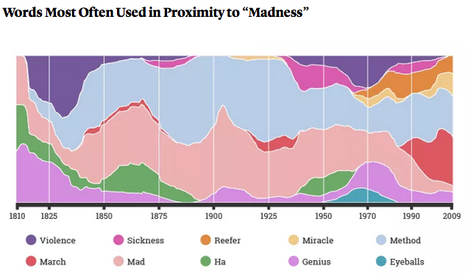

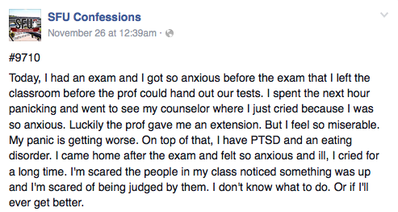

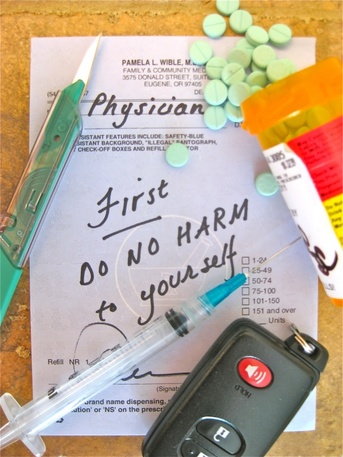

In Detroit, Michigan, the Henry Ford Health System has instituted a new suicide prevention care program, which aims to reduce the suicide rate to zero through taking on a more proactive approach to depression and self-harm. The program, which begins with primary care physicians screening every patient, has already led to suicide rates that are well below the national average, more positive patient experiences and consistency and continuity between healthcare providers, as well as significant healthcare savings due to the reductions in ER visits and hospitalizations. Though innovative in their approach, the new initiative is now a model that other communities should be shaping their suicide prevention services after ... "The plan it developed is intensive and thorough, an almost cookbook approach. Primary care doctors screen every patient with two questions: How often have you felt down in the past two weeks? And how often have you felt little pleasure in doing things? A high score leads to more questions about sleep disturbances, changes in appetite, thoughts of hurting oneself. All patients are questioned on every visit. If the health providers recognize a mental health problem, patients are assigned to appropriate care — cognitive behavioral therapy, drugs, group counseling, or hospitalization if necessary. On each patient's medical record, providers have to attest to having done the screening, and they record plans for any needed care. Therapists involve patients' families, and ask them to remove guns or other means of suicide from their homes. Clerks are trained to make sure that patients who need followup care don't leave without an appointment. Patients themselves come up with "safety plans."" For the full article, click here: http://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2015/11/02/452658644/what-happens-if-you-try-to-prevent-every-single-suicide  In this fascinating article, we learn the history behind some of vocabulary used to describe mental health or those affected by mental illnesses, including the terms "neurosis", "mental", and "madness", as well as how our use of these words has evolved over time ... "According to the Wellcome Trust, the rise of the term mental health was largely due to the efforts of early 20th-century social reformers, who wanted to reduce the stigma attached to people who had been deemed mentally unwell. Whereas mental illness set up a verbal division between the healthy and the sick, the term mental health implied more of a continuum, a state that could improve or degrade in anyone over time. If mental health is one of the newest tools that modern English has for describing the condition of the mind, then madness is one of the oldest." For the full article, click here: http://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2015/10/mental-health-words/412630/  Online there exists numerous "Confessions" Facebook pages for most Canadian universities including Dalhousie University, McMaster University, and even the University of Toronto where students can share anonymous confessions ranging from the humorous to more troubling and serious issues. Recently, an article shed light on one of the largest Facebook pages, SFU Confessions, where students have been anonymously submitting stories of depression, anxiety, and suicide attempts and ideation. In this interesting article (link below) the author suggests that though it is important for students to openly discuss their mental health issues, the anonymous means Facebook pages such as these provides, only serves to continue perpetuating stigma and fails to help truly support students and connect them to appropriate supports and resources. Rather, the author suggests, we should be encouraging students to have "meaningful" and personal conversations about mental illness with family, friends, or mental health services on campus or in our communities. What do you think about the issues discussed in this article? Do you think anonymous web or Facebook pages are appropriate or helpful outlets for those facing mental health challenges? "If individuals are encouraged to only share their struggles when they can fear no social repercussions, then instead of challenging the belief that talking about mental health is shameful or embarrassing, it perpetuates that stigma. Instead of being able to put a face to mental health issues, there remains a shroud of secrecy." For the full article, click here: http://www.the-peak.ca/2015/11/sfus-culture-of-confessions-obscures-mental-health-issues/  Last week, tragically, a 27-year-old internal medicine resident at the University of Montreal died by suicide. While this young and promising new physician was not the first doctor to die by suicide, her loss reminds us of the persistent issue of mental illness, as well as the high pressures, stress, and burnout that face those entering the medical profession. While we have become aware that 1 in 7 medical students have contemplated #suicide and that "we lose at least one medical school worth of MDs per year to suicide", little has been done to address the persistent stigma of mental illness among healthcare professionals, or the culture of medicine that tends to perpetuate burnout and depression. As this powerful article by Andre Picard emphasizes, it is time to now transcend from increasing awareness to focusing on actually taking action and addressing and preventing mental health issues among our medical students, residents, and physicians, as suicide and mental illness should not be an occupational hazard of the field. "In short, medical education is too often imbued with a macho attitude that learners have to be broken down and toughened up and that those who can’t take it are weak and unworthy. Perversely, many physicians take pride in this boot-camp mentality. When efforts were made to eliminate the insane 100-hour workweeks of residents, old-timers quietly (and sometimes not so quietly) dismissed the younger generation as wimps... In fact, what’s different today is not that young people are weaker, it is that expectations are so much higher and isolation is so much greater, in spite of (or perhaps because of) so-called social media. Medical students and residents are also headed into a world of uncertainty, not one where they are guaranteed a life of privilege." For the full article, click here: http://www.theglobeandmail.com/globe-debate/suicide-should-not-be-an-occupational-hazard-for-doctors/article27444903/  Poet Maya Angelou during her childhood, suffered from selective mutism, a type of anxiety disorder that often presents in children. In many cases selective mutism is also associated with shyness or social anxiety, and affected individuals experience great fear in specific situations where they are expected to speak, such as at school, rendering them silent. In this unique and descriptive poem by Carl Sutton, we get a glimpse into what it's like to live with this condition that can be quite impairing ... "Some days the rusted door is left ajar, and out the shadows of my whispers waft - my face is near but voice is from afar at first, but then I sing and hoot aloft. Some days I hoot of silence to the sun..." For the full poem click here: http://www.ispeak.org.uk/Awareness2015.aspx  While once rated one of the "happiest" countries in the world, it is not so surprising then that in North Korea mental illness is rarely discussed or heard of outside of politics. However, in this interesting article below we gain a greater understanding of the mental health system in North Korea and how common mental illnesses are managed from isolating those with schizophrenia to treating depression as a physical rather than emotional or mental illness. "Internal medicine doctors and neurologists rather than psychiatrists treat what are considered the less serious cases of mental duress. The North Koreans do not have a real concept of depression; the media rarely even use the term unless they are projecting it as one of a number of sicknesses endemic to a bourgeois capitalist society like America. Instead, the preferred terms for any kind of neuroticism are cardiac neurosis and neurasthenia (an outdated category of diagnosis in modern psychiatry). Conditions such as prolonged anxiety, insomnia or fatigue that in the West one might associate with a psychological condition are considered physical rather than mental ailments, and the treatment such as herbal medicine accordingly targets the body more than the mind." For the full article click here: http://www.nknews.org/2014/12/a-look-into-the-dprk-mental-health-system/  While there are no official studies detailing the precise number of med students with mental health issues in Canada, data from elsewhere around the world suggests that the rate of depression among medical students can reach as high as 20% or 1 in 5. Though each university offers wellness services for their students, University of Western Ontario is the first to hold peer-to-peer forums where medical students come together to discuss stress and their personal mental health experiences including eating disorders, suicidal ideation, self-harm, depression and anxiety. The idea behind such peer forums are to help overcome the stigma of seeking help, for students to understand that they are not alone with regards to burn-out and mental illness, and to provide support, hope, and encouragement to one another. "Chitpin estimates that at least half of the students who attended the forum have, or have had, mental health struggles. In interviews, Chitpin, Sauvé and other students stated that they have to feel safe talking about what's going on inside their minds. They said they become more comfortable discussing their problems when they hear classmates share their personal mental health experiences. Having one or two trusted friends or classmates can often provide vital support." Read the full story here: http://www.cmaj.ca/site/earlyreleases/10nov15_medical-students-talk-openly-about-their-mental-cmaj.109-5151.xhtml  A new study has found that suicide occurs more often in rural regions than urban centers. The article below investigates some of the reasons those who live in smaller, more remote towns, are at higher risk of suicide including higher rates of gun ownership, avoiding seeking help due to a lack of privacy, and most especially a lack of access to mental health services and supports. The article also speaks to addressing the issue of access through integrating mental health into family medicine practices and utilizing telepsychiatry. "Rural suicide arises from all the circumstances Ms. Barrasso noted and more. Despite a sleepy “Mayberry” sort of image, the realities of small-town life can take an outsize toll on the vulnerable. A combination of lower incomes, greater isolation, family issues and health problems can lead people to be consumed by day-to-day struggles, said Emily Selby-Nelson, a psychologist at Cabin Creek Health Systems, which provides health care in the rural hills of West Virginia. “Rather than say, ‘I need help,’ they keep working and they get overwhelmed. They can start to think they are a burden on their family and lose hope.”" To read the full article, click here: http://www.nytimes.com/2015/11/03/health/small-towns-face-rising-suicide-rates.html?smid=nythealth&smtyp=cur&_r=1 |

Description

Supporting and enhancing students' and health professionals' knowledge and understanding of mental health and psychiatry

Archives

June 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed